How My Daughter Saved Me (From the pain of old wounds).

God has a sense of humour. And nothing like showing complete strangers your most deeply buried insecurities. That headline is way too long :)

My daughter Georgina1 crossed the stage and graduated from high school today. Georgina is a beautiful girl, and I believe my assessment is more than the bias of a proud father; I see her as a child born of an ironic God, for she is the progeny of a father whose childhood was framed by years of taunts of “ugly, freak, living abortion, and monster.”

Even today, I vividly remember opening a door at a family friend’s house over forty years ago and stepping into someone else’s conversation. When the door opened, the words hung brightly, suspended; six breaths were drawn in, and diaphragms were paralysed for a pregnant second.

“Their puppy is cute, but Paul is so ugly, a complete freak. Not human.”

I spent the evening in a basement corner, squeezed between a chest freezer and the wall. People say sticks and stones, but I was seven; it was as if my tribe had gathered together to face me on the edge of a great forest, and they had banished me. I thought I was safe amongst friends.

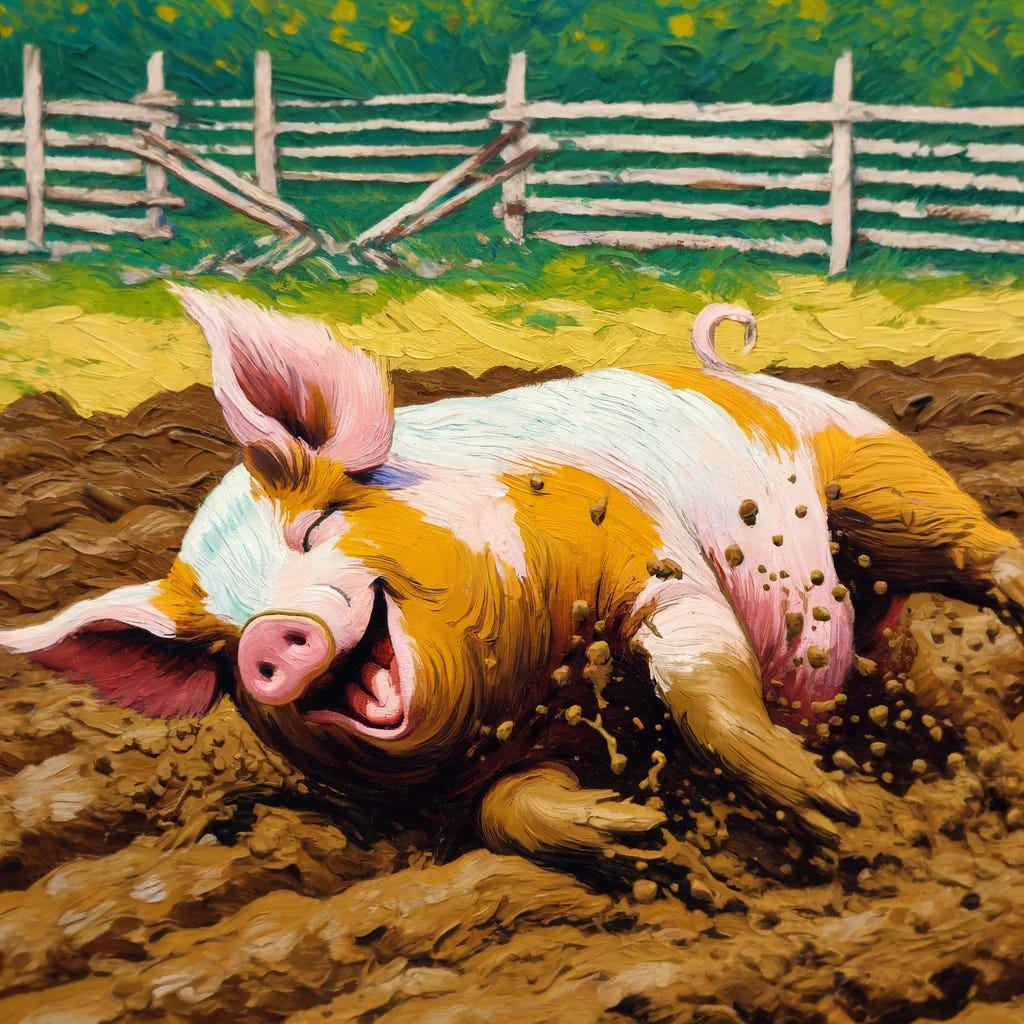

But today, Georgina is beautiful, and God has a sense of humour. And I will stomp and roll, like a joyous pig - in all the glories of my vicarious mud wallow.

Georgina was born with red hair, but ginger turned strawberry blonde, and she has now gently moved to be a light blonde. Though my adopted parents said I was a blond baby, red followed, and today, my red beard is all that remains; it is the only trace of what Mormon sites dedicated to tracing lineage say is 600 years of Irish ancestry.

It pleases me that my daughter has so many friends; I am never so content as when she has a household full of them, or even just one, to hear the muffled happy chatter behind her bedroom door. Yet, while it brings me back to my Winnipeg bedroom, with the built-in long blue desk and the small homemade and disassembled bunk bed with only the lower half remaining,

My bedroom was a place to hide, a bomb shelter of sorts; I remember being disconsolate, lying face down, perhaps 11 or 12; it was after the chorus of insults from the new private school bus kids; they said, ugly, mutant, inhuman freak, they positively howled as I ran from the bus; but soon after dad sat on the foot of bed, stroking my legs, quiet but present. The taunts were not isolated or random but dominated my childhood, like walking thigh-deep along an ocean’s edge. The revilements were waves, and happy people on the shoreline shouted at me to keep going and warned me not to get wet.

But today, the generation's genetic doors are closed; nothing has slipped through the door's seal. Georgina is safe. Her room is often a social space, not a bomb shelter to hide from the cruelties of youth. I thank God the generational jump has broken the cord of pain.

She has had a boyfriend for over a year. He is from a good, respectful family and treats my daughter well. When I saw them depart for her prom, I looked him in the eye and said, “Take good care of her.”

That is all I want, my beautiful, precious daughter; she is still a baby who has grown; the first howl of indignation the moment she was removed from her mother’s womb still echoes in my mind. Memories are not video; they are pictures full of triggers, retrieved through mysterious combinations of sensory inputs and emotion.

At the formal graduation, I sat with her boyfriend; the graduation ceremony was the typical stream of platitudinous speeches, many awards, politicians I had never heard of, and Catholic references to God that seemed largely ignored. The valedictorian speeches won me over, not by their wisdom, but by their confidence, their assuredness in their community, and sincerity not crafted by parental dictates - the organic eruptions of applause showing the leafy flowers of youthful optimism.

Perhaps it was a youthful spirit I never had, but I am comforted that I am not everyone; optimism is not extinct. Indeed, confidence roared in that room full of students, parents, family and friends at Joan of Arc High School.

Georgina crossed the stage, an Ontario Scholar and Honour Roll, and then was gone, gracefully walking to the end of the stage, avoiding the grad fear of heel collapse. As she walked away, I remember the sadness I felt leaving her as a child, a tiny redhead with cropped hair, dutifully standing in line when she started fourth grade at her new school in Peterborough. She was small but stood firm and obedient, not turning to me, resolved to face her newness and not hoping for me to pull her out of the line.

At that Peterborough school, I stood on the edge of the basketball court. I watched Georgina walk into school under the heavy stone archway, shepherded by a middle-aged, brown-haired teacher in an orange vest. The teacher was overseeing her new children with the attentiveness of a circling tiger, watching her cubs venture out of the safety of their cave. At that moment, I was comforted; it was clear that the orange-vested teacher saw not just another group of students; they were her children, and she guarded them fiercely.

Watching my daughter triggered more memories of my older son Liam’s first day of kindergarten in Fort McMurray. We had not said a proper goodbye; he had been caught up in a line, but a frantic teacher ran after me, calling my name.

Where was this father walking away? The teacher must have wondered who this little boy’s dad was. But she had no concerns for social conventions; she shouted down the sidewalk, “Paul, come back!!!”; she was determined to find the parent of her weeping four-year-old.

I turned to face the teacher and ran back to comfort Liam.

The teacher said he was crying; the words crimped between her gasps for air. “He said you didn’t say a proper goodbye,” I found him red-eyed and small and held him tight. The teachers were kind, and I saw nothing of the strict ideologues encountered in the media.

In this last week of June, my daughter has fully embraced and glorified the prom excitement. At prom, she wore a light purple dress; she will likely only wear it once, but this is fine. Her boyfriend brought a set of dark eggshell white rose boutonnieres, now accompanied by velcro attachments.

I remembered how Georgina and I recently flew to Calgary and rented a car to go to Vulcan, AB, intent on seeing my father’s grave on the first anniversary of his death. Georgina stood uncomplaining in the cold behind me and helped me find my father’s graveyard in a deep snow-filled field where flat graves were undistinguished from the surrounding land. But the windshield scraper sufficed, and I found my father’s grave marker. The date of birth was now accompanied by the date of death; I turned and saw my daughter right behind me, shaking and crying, consumed by grief, her young heart facing its first experience of death - but we were together; we clung together as we wept.

On Georgina’s prom day, I dropped her off at her best friend’s house, a gathering point before the grads took a party bus together to the banquet hall; even with the confidence brought by my best and only suit, I felt assured I would not belong.

The parents of other graduates sat around a back table, and the boyfriends, many I had already met and forgotten, reintroduced themselves and shook my hand. The room was full of thousands of bursts of excited chatter, teens dressed in their best suits and bright-coloured dresses, the confidence rising like tiny red shoots of light, scattered like fireworks, chasing the heavens, only to fade quickly and be replaced by a yellow one, a green, a soft purple ray that was lost and falling.

The parents, primarily Italian, with a Chilian fellow eager to chat, welcomed me, perhaps sensing my awkwardness. I was not a man who smiled easily. My daughter, though, could quickly turn a smile for a camera. My childish insecurities have forever robbed me of that ability.

On Georgina’s prom day, I was the only adult who wore a suit, my only suit, the funeral suit, the wedding suit, and the suit that worked at a political fundraiser. The assembled parents seemed old friends, or they bonded quickly and easily; there were no stiff formalities; I feared them asking what I did; I did not want to float the pompous, “I’m a professor,” as if it would make me look stuffy, nor did I want to tell them I was a suspended professor, a man who had declared he stood with Israel and who had dared call the killers of children at the Nova concert Nazis; but were they not the same ages of these 17 and 18-year-olds assembling for this prom?

Yes, I was right to name-call those killers Nazis.

Apparently, after seven months of suspension, with no word allowed in defence, - the University of Guelph says my words are nevertheless a firing offence. The accusers’ calling for the extermination of Israel, posting speakers who accused Jews of trafficking in human body parts, and saying Jews were sub-human - all such comments were tolerated; at the University of Guelph, they brought no offence to unknown administrators, so many hid behind titles, emails and subordinates.

But my objections and indignant reaction to those who flew in with hang-gliders and machine-gunned barefoot children at the Nova concert who were dancing on the grass - such was not allowed.

But still, on my daughter’s prom day, I felt like a fraud. After forgetting another name and covering my embarrassment with a joke about Alzheimer's, I sat down. The table was generously covered with untouched round plastic platters of Costco-cut fruit, delicate Italian pastries, cans of Stella Artois, and alcoholized mineral water that tasted like water and vodka.

As a professor/lecturer, I have no issue meeting a room of 19-year-olds, but I felt awkward amongst the parents and had an overwhelming sense of not belonging. Part of it was being 59 years old, ancient for a parent of a 17-year-old daughter, even if her 18th birthday was only a few weeks away.

Feelings of fraudulence ramped up as I sat down, gulping my beer. The beer at least offered some familiarity; the nervousness and perhaps some face recognition issues reared up again as I introduced myself to the host's wife for a second time, even though I was stone-cold sober, and all within the first five minutes.

At the table, the conversation evolved to include reminiscences of long past high school graduations - my heart twinged. Embarrassment is a sculking beast; it finds a place to hide and is content to stay there for years, but with a few words, a conversational tilt and there, the little bastard wakes and pinches the heart. I remember my prom and my grad. My mother had cancer, and it was just a few years from taking her down; my childhood had enough events that left me thinking I was so freakish that I needed to self-incarcerate in my room. I remember the school bus ride’s collective shouts of being “a living abortion,” a youthful, wretched social contagion of speech that smothered esteem.

Even now, it echoes in my heart. 45 years.

Back then, I would sit at my bedroom desk, the blue built-in one my mother had special ordered for me, and I would draw hideous caricatures of myself—the buck teeth, the fish lips, the random spattering of freckles. I had convinced myself—and it seems so foolish now—that I could not walk in public company. But it was well enforced by so many around me. It was no random judgment.

For me, a date at prom was unthinkable and impossible. I was lucky to be allowed to walk the earth untormented.

Memory is a curious thing. It is not video; it is covered in smells, colours, emotion and other sensory inputs, and it can come back, not sterile and colourless - but neither as bright as originally wrought.

My prom, where I was one of the few ones dateless, was a walk of fear and insecurity; at my last school dance, I had found a date: Peggy. I was fond of her, but she ran into an old boyfriend at the dance and left with him for two hours, returning in time for me to give her a ride home.

The two-hour vanishing sucked the romantic air out of the car; I only heard the mocking voice of fate that I had heard in my bedroom, bitterly drawing caricatures of myself and telling myself that this romance game was one I was not allowed to play.

As I pulled up in my Dodge Coronet 440 to drop Peggy off, my heart broke into fragments of humiliation. They lay on the plastic winter mat, right next to stalks of wheat that had fallen when my dad and grandfather inspected our fields near Vulcan, AB.

My humiliation didn’t bring tears, just an empty gut, the same feeling I had sitting on the basement orange couch, still in my prom suit, 9:00 PM, though wishing it was later, having escaped the prom through a side door, unable to deal with the humiliation of being dateless and consumed with gnawing insecurity, out of place in a space that seemed to burst with confidence and contentment; full of young men wearing cheap Sears suits, bright ties skewed to the side and boutonnieres now barely clinging to lapels, the petals starting to fall.

But today, my daughter glows; there seems to be no anxiety; no genetic curse has thrust itself on her. There is no desperate drive to end it all, no “the best part of any social occasion is always leaving,” no relief to have made it through, off to return to a “safer space” - all this that had consumed my teenage years was gloriously absent.

I am grateful that my daughter is not living the memories unearthed in me recently.

Ezekial says the child will not share the parent's guilt, and the parent will not share the child's guilt. I am thankful for this.

God has blessed me, and I am so grateful for my daughter, who is content and secure during her prom and graduation. My demons stayed home in my Winnipeg home that I left at 19, and today, my faded childhood memories have lost their sting.

Not her real name.

How wonderful to have had the experience of seeing your beautiful daughter comfortable in her own skin. Your love made that happen. You write so compellingly about your painful childhood and I am glad the sting is largely gone. “What doesn’t kill you [made] you stronger?” Childhood can be painful, and it sounds like yours was peopled by an abundance of bullies. I imagine you have studied the psychology of bullying, and maybe that provided some comfort, too. I’m watching six grandkids go through it all these days, and feeling glad I only had to do it once. The U. of Guelph’s treatment of you is another story, and inexcusable, as is the antisemitism and hate speech being tolerated almost everywhere. Thank you, again, for calling out the perpetrators of October 7th. Please know that I am in your corner! A big Mazal Tov on your daughter’s graduation. May you both go from strength to strength!