From Evin Prison to Israel Advocate: The Remarkable Journey of Salman Sima

by Dave Gordon

If you believe in the importance of free speech, subscribe to support uncensored, fearless writing—the more people who pay, the more time I can devote to this. Free speech matters. I am a university professor suspended because of a free speech issue, so I am not speaking from the bleachers. The button below takes you to that story.

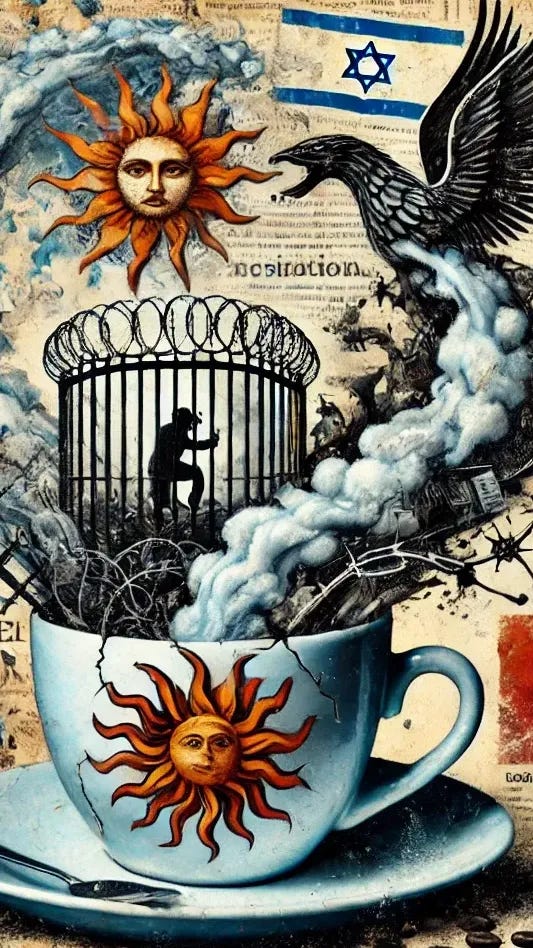

Please subscribe to receive at least three pieces /essays per week with open comments. It’s $6 per month, less than USD 4. Everyone says, "Hey, it’s just a cup of coffee," but I ask that you please choose mine when you choose your coffee. Cheers.

Salman Sima is an Iranian-Canadian activist and former political prisoner of Iran who has become a prominent voice against the Islamic regime and an advocate for Israel. Born in Zanjan, Iran, Sima was a student activist who organized protests and published a critical student journal, leading to his first arrest in 2008.

Michael Mostyn, MP Melissa Lantsman, Salman Sima and MPP Laura Smith at a Toronto synagogue discussion on the rise of antisemitism- Photo courtesy Sima

Sima was imprisoned three times in Iran's notorious Evin Prison, specifically in the 209 ward under the supervision of the Intelligence Ministry. He endured solitary confinement, limited access to basic hygiene, and psychological torture. Despite these hardships, Sima remained resolute in his opposition to the regime.

Facing a six-year prison sentence, Sima made the difficult decision to flee Iran in 2010. He escaped through the northern border into Turkey, where he sought asylum with the UNHCR. After nine months in Turkey, Sima immigrated to Canada, arriving in Montreal and settling in Toronto.

Sima quickly resumed his activism in Canada, participating in protests and counter-demonstrations against pro-regime events like the Al-Quds Day rally. Initially harbouring some hesitation towards Israel due to years of anti-Israeli propaganda in Iran, Sima's perspective changed after interactions with Israeli supporters at these events.

Sima has since become a vocal advocate for Israel and human rights, campaigning to shut down the Iranian regime's embassy in Ottawa and to list the IRGC as a terrorist organization. He continues to fight against antisemitism and the Iranian regime and is often seen as a fixture at pro-Israel rallies or protesting pro-Hamas demonstrations.

He remains committed to the cause of freedom in Iran and hopes to return to his homeland one day.

In this wide-ranging Q&A, Salman Sima discusses his time in Evin’s notorious prison system in Iran, his activism against the Islamic regime, his advocacy for Israel, and his long, painful journey to make a home in Canada.

I want to know what it was like living in Iran before you came to Canada.

You are living in a country where you don't have social freedom you don't have political freedom; not just only that, the government is incompetent. Public transportation is not good in Iran. The roads are not safe. You don't have democracy, you don't have free speech, no human rights. But the only pleasant experience for me was being with my family and being among friends.

Were you taught in schools to hate the West, to hate America, to hate Israel?

I do remember at seven years old, we were made to chant “Death to Israel, death to America.” On national TV, they broadcasted the chant, even death, to the UK. You know, they brainwash you in the movies, TV, and radio. Imagine you are a seven-year-old kid, and every morning, you are made to chant this.

In 1980, they made children celebrate the anniversary of taking the US diplomats as hostages and the attack on the US embassy in Tehran. These days, thanks to social media, they cannot brainwash as much.

Why were you sent to Evin Prison?

In 1999, students in Iran staged the Hijdah Tir uprising, protesting the reformist government of the time and saying that it was fake. The regime crushed that uprising.

On the 10th anniversary of that uprising, I was organizing a protest at my university to remember the 10th anniversary of that uprising. Then, before I could protest, they arrested my friends and later me in the summer of 2008 because I wanted to carry the torch from the previous students’ uprising against the regime.

And at that time, I had a student journal. They banned my journal from our university because I exposed some of the corruption of the Dean of the University and criticized the regime. Then they came after me. They banned my journal. They temporarily banned me from my bachelor’s degree for two semesters.

How many times did you go to prison?

I was arrested 13 times between 2008 and 2010. I was put in jail three times.

What was jail like? What was Evin's prison like?

It depends on which ward you are assigned to. Most of the time, I was assigned to the 209 ward, which the Intelligence Ministry supervised. The Intelligence Ministry usually supervised me.

I was in a room, say, two meters and a half by four. At the end of the corridor is a washroom, and they open your cell thrice daily, each time for 10 seconds. They give you a very small breakfast. I always was hungry. All of a sudden, you don't have anyone to talk with. Then they put you in a cell for a long time, 10 days, 20 days. And you need to consider that when you are alone in solitary confinement, you have nothing to do. You even count the ants, the small bugs in your cell – you count that because you have nothing to do.

So then, when they bring you for an interrogation session, you are willing to talk because you haven’t spoken with anyone for a long time. This is some kind of torture when they tell you you’re forgotten. It was all a lie. Because after I was released, I saw that my father advocated for me 24 hours, seven days a week. My friends celebrated my birthday in my absence. Amnesty International issued a statement, and Human Rights Watch stated me too.

Were you given any access to hygiene, like a toothbrush or a shower and so on?

When you are in solitary confinement, according to the prison law, they should give you a brush and a towel or something like that at the beginning of your entrance. But there is no real supervising. They gave me my brush after a few days. But you have two showers a week in 209 wards at my time. And the shower was so cold. Each time,e five minutes, maximum 10 minutes.

Was it difficult to immigrate? How did you leave Iran? What was the procedure like?

I had many good friends, and I still miss them... For me, deciding to escape the country in 2010 wasn't easy. And I had a six-year sentence by a brutal judge, Aboqasem Salavati, who the EU sanctioned and, unfortunately, is not sanctioned by the Canadian government.

My lawyer told me that I had to escape or face six years in prison—lots of pressure from my family, who couldn’t bear the thought of seeing me behind bars.

Some of my closest friends, they said: “Salman, you have to go. Because if you go, you can be our voice, but if you go to prison, you will be another load on our shoulders. And for the sake of freedom, you have to go.” And still, I couldn't convince myself. So it was really difficult for me to decide. And up to this day, one of my motivations to fight antisemitism, fighting with IRGC, is that I feel guilty for leaving the country and leaving my close friends.

It's still very emotional right now, and it was a hard decision, but I chose freedom.

I don't know when I will return to my country, but I do know that one day, even if I am 100 years old, I will.

Here in Canada, I campaigned to shut down the Embassy of the regime in Ottawa, I campaigned to list IRGC on the terror list, and I campaigned to list Samidoun as a terror entity. I couldn’t do any of this in Iran.

So, I took a bus with a fake name from Tehran to Zanjan, the city of my birth, 300 kilometres west of Tehran. I said goodbye to my relatives—the grandfathers I would never see again, as I had lost both of them while I was in Canada. I just hugged them as much as I could.

I found a smuggler from the northern border of Iran and Turkey. Then, I went to Urmia, another major city, and Khoy. When a smuggler welcomed me, he hid me in his home for two days; then we drove to the mountains. Then we changed the car. We went on a pickup truck to the mountains. I remember we were in the back of the pickup truck, with blankets, some weeds, and some garbage over us to hide ourselves. I remember how cold it was.

After the pickup truck, I went to a village and met a good smuggler who gave me honey and butter. These are the best honey and butter I have ever had. They are organic and 100% tasty. I ate like a cow, knowing it could be my last meal.

We went up to our knees for four hours on a walk in a river. I met another smuggler, a petroleum smuggler, coming from Turkey to Iran's border with horses. They gave us their mules, and we travelled six hours. So, at that moment, I understood that the smuggler's job was smuggling the gas, and we were a side business for him.

We then passed the Turkish border. It was a beautiful wheat farm with tall wheat bushes. Everything was golden. We were too tired to move one hour before sunrise, so we lay down. After two hours, the cousin of the main smuggler picked us up and gave us a ride to Van, the major Turkish city close to Iran's border.

There were several checkpoints by Turkish police and the Turkish army.

So we passed the checkpoints, and then he dropped us in a van and took us 45 minutes to walk to the UNHCR office. They interviewed me for two hours.

Then they gave me a bayaz card, which means white ID. Then I was asylum at that moment, and no one could deport me legally. I did another interview in six months with the UN and another interview with the Canadian embassy in Ankara, the capital of Turkey. Then, nine months after arriving in Turkey, I travelled from Istanbul to Montreal. I came to Toronto two days later.