Red Coat in a Foreign Winter

A young doctor, a child in tow, and a fight that could end in triumph—or heartbreak.

They say it’s “just the price of a coffee.” Spare me. You already have too much caffeine in your bloodstream. What you don’t have is enough fearless prose that refuses to grovel before the cult of feelings. For $6 a month, less than USD $4, you can remedy that.

But I only ask that when you choose your coffee, please choose mine. Cheers.

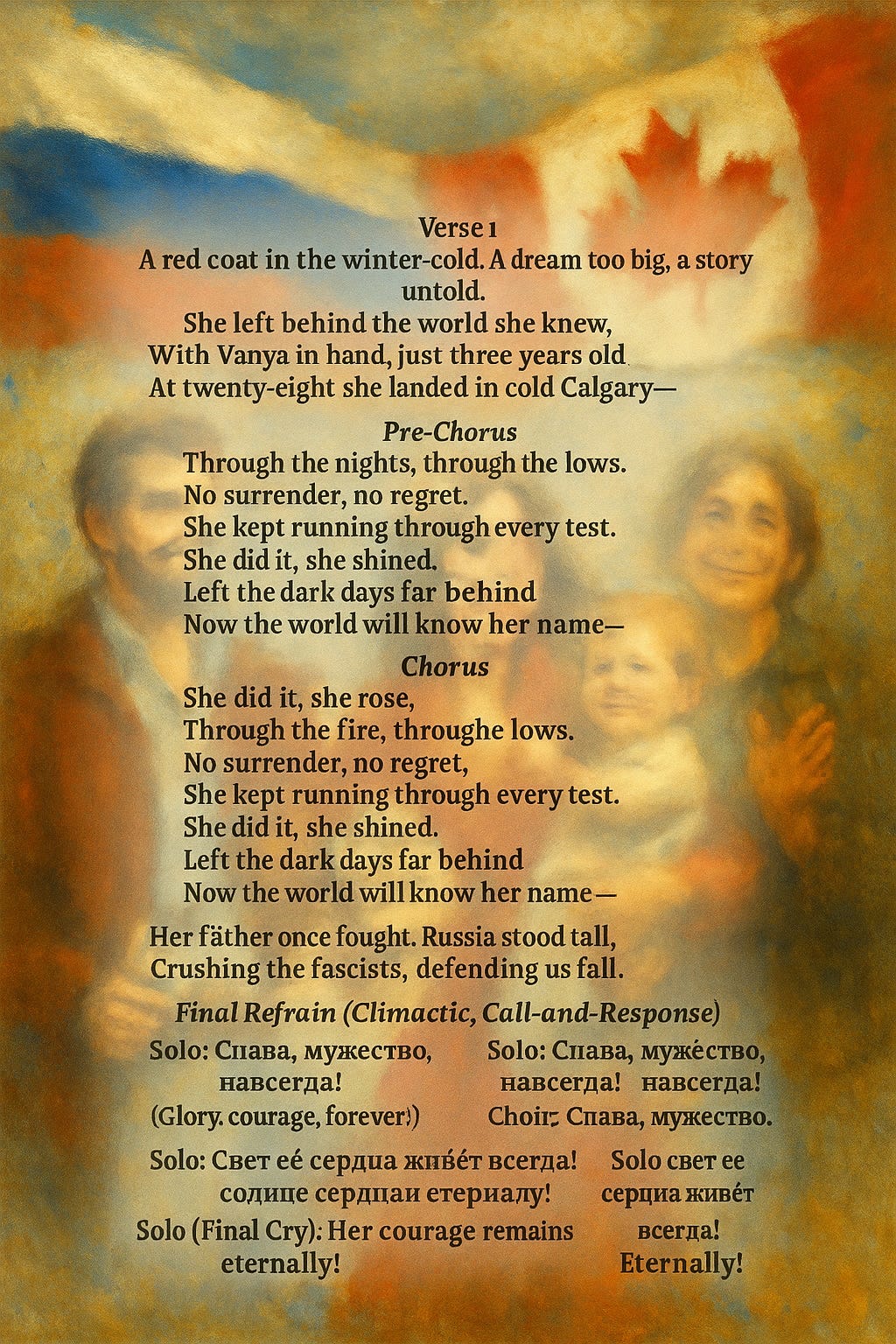

This is a song I wrote to go with it. Adding a song with AI (my lyrics) to an essay is a bit odd, but I have never claimed to be normal.

This piece is intensely personal, and dear reader, I ask one favour: please listen to the song I wrote about my wife, available below.

It is so hard to come from Russia to Canada and make it as a doctor; the system was cruel at times, but she, and we, fought through it. I love her and will always be immensely proud of her. She attended medical school in Russia and lived in a room infested with cockroaches, but never complained.

She came to Canada, fought rejection, studied hard, and made it, and became a Neurologist in Canada—lyrics at the end of the essay.

She was a neurologist in Russia, but studied for two years to get her residency here.

When we first met in St. Petersburg, Russia, Olya wore a thick, red felt coat and barely said a word. “Kak dela?”—my phonetically challenged attempt at “How are you?”—brought a quick smile.

She was a neurologist working for a hospital in Veliky Novgorod, a 1,100-year-old city north of Moscow. She lived with her mother and infant son, Vanya, on the second floor in a Stalin-era apartment block, one of a horseshoe circle of identical units, four stories each, inside with curved railings worn smooth by the palms of thousands of weary Russians climbing the stony steps. The faded green railings had the colour of leaves at the bottom of a spring puddle.

Next door was a 900-year-old, bright white plaster Orthodox church. Church that had been reassembled after World War II, its windows coated with dust and covered by cardboard.

Her blond two-year-old Vanya met me at their apartment door, wearing well-ironed checked pants, standing wide-footed and cross-armed in a small red bowtie.

Within minutes, Vanya was on my lap, his man-of-the-house bravado broken down by chocolate and orange juice, and I was pouring (and spilling) champagne on my future mother-in-law.

Vanya and I fell in love. We would go for walks in the park, where old Russian women would stop us and fix Vanya’s scarf. Vanya did not speak a word of English, and I knew only a handful of Russian words, but no matter—we loved each other.

When I would leave Vanya and Olya at night to go back to my hotel, Vanya would cry and tug at me, sometimes pulling the shoelaces from my shoes in a desperate bid to stop me from leaving.

Over the next two years, I travelled seven times to Russia, staying in Novgorod while my future wife worked at the hospital.

We married in Russia; the Canadian government gave us no choice. It was a tiny ceremony at the community hall; the state did not allow church weddings. I gave the clerk a bottle of wine and said “pa-dark,” my butchered Russian for “gift.”

There was a small orchestra at the reception. I foolishly tried to outdrink her father and got very drunk. The orchestra played on, and we lit fireworks. Vanya ran into my arms wearing his crisp white shirt, black bowtie, and Manchester United football shorts I had brought him from Canada.

Fireworks exploded; nothing was burned down, no one was hurt, and soon it was over. The suit was returned, and after a honeymoon, I was back in Canada.

A month later, Olya and Vanya stepped off the plane in Fort McMurray, Alberta, where I worked as a college instructor.

Olya’s first task was to understand what the government required for her to become a Canadian neurologist. Without my help, she set up an appointment at the local hospital to meet the medical director.

She returned in tears.

He hadn’t shown up, leaving only a message for her to speak with a nurse. But she pressed on. The College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta told her that her residency wasn’t up to Canadian standards but allowed her to write an evaluation exam, which she passed.

Soon, she was off to Saskatoon for a second exam. When I picked her up at the airport, she was disconsolate and weeping, convinced she had failed. But she passed, and when I looked it up, I discovered that her score in her speciality was in the top one per cent.

My new job in central Canada beckoned, in a city whose hospital offered residency opportunities. After four days of driving across Canada and through the Canadian Shield in a 12-year-old Honda Civic with a deer whistle and a half-attached front bumper, we arrived in London, Ontario.

Olya was seven months pregnant, and while I worked, she studied diligently, except for two daily three-kilometre round trips to take Vanya to kindergarten. The binding on her copy of Toronto Notes had long since failed, now held together by duct tape and tender care. She was studying when I left at 7 AM, and equally, when I returned, she soldiered on.

Our daughter was born in the heat of July.

Olya brought her Toronto Notes medical textbook to the hospital and told me she might as well study, as her neighbour kept the light on at night.

With our newborn red-headed daughter at home, I returned each evening to find Olya studying, still buried deep in our brown-stuffed couch, Sophia resting by her side.

More than good grades on additional exams were needed to get a residency—Olya needed to volunteer. One of my co-workers set her up with a local paediatrician, a tiny, kindly Zoroastrian lady. Another contact from a neighbour led to a volunteer research project. A Canadian lawyer notarised all her documents free of charge.

Many nights, I woke to the light from the office. Olya forever studied—her textbooks spread across the table my grandmother had brought from Ireland, the battered Toronto Notes open at the foot of the couch.

My father told me how his own father, who had only finished Grade 8, helped support my uncle, who became a urologist in Calgary. My father continued the tradition and paid Olya’s exam and book fees.

After two years of studying, Olya was pleased to find she had nine residency interviews. So we went off to buy proper medical resident interview clothing. In the early spring, we drove from Waterloo, Ontario, to Kingston, London, Ottawa, Hamilton, and Toronto.

There was so much weight on her, on us all, as if we were standing behind a wall falling in. Anxiety gnawed at me, and of course, for Olya it was worse. Everywhere we went, we heard stories of applicants who had travelled thousands of kilometres for their one opportunity, some in their sixth year of trying, others respected physicians in their home countries but now waiting nervously to interview in a room filled with equally qualified candidates.

At the University of Toronto, Olya left the interview room feeling confident. One of the interviewing doctors eyed me strangely, perhaps assuming I was another candidate and wondering why I was wearing jeans. I introduced myself as Olya’s husband, and the doctor laughed.

Olya told me later that they had asked how she would respond to taking directions from younger residents, as she was an “ancient” 28. “I’m not that old,” she replied. They thought that was spunky.

The day of the residency match came two months later. After two and a half years of study, Olya would be informed by logging on to a website.

At work, I waited for her call, fearing the sound of a quivering voice and tears. Only a few applicants receive a residency.

She was matched at the University of Toronto.

Her mother, who had come from Russia, cried joyfully as she tried to explain to her grandchildren how much their mother had accomplished. We cried too—hell, I cry now reading this. I was proud as I drove home with a bottle of wine.

My immigrant wife was now a neurology resident.

So many immigrants with medical or professional degrees end up working menial jobs. But she had run the gauntlet and emerged wearing scrubs.

Today, Olya has a thriving practice in Toronto. Nineteen-year-old Sophia is doing well at university, and Vanya is an engineering student at Carleton. He no longer supports Manchester United.

I teach or taught at the university, write for Substack—though I was just fired for offending Hamas and their backers at the University of Guelph. My children are now 19 and 24.

I mostly work from home and care for my two beloved Westie terriers, Toby and Malibu.

My daughter, born in the heat of July, has grown up.

My wife practises in Toronto; my father, who passed away recently, said he was amazed at her heart and perseverance. She did it; she rose through the fire, through the lows, with no surrender, no regret. I will always be proud of my wife, my love.

Слава, мужество, навсегда! (Glory, courage, forever!)

Choir: Слава, мужество, навсегда!

Свет её сердца живёт всегда!

(The light of her heart will live forever!)

Choir: Свет её сердца живёт всегда!

Solo (Final Cry): Her courage remains eternally!

Choir (Echo): Eternally!

Thx

Thank you for sharing your story. You have a brave wife, and sounds like a wonderful family. Congratulations.