The Cruise Ship of the Mind

Our Civilization Sleeps as the Course Changes Beneath Us

If you’ve made it this far in life without being fired, cancelled, or publicly flogged for saying something true, congratulations — you’re ahead of me. I write because I can’t not; because silence feels like complicity, and complicity feels like rot. If this piece leaves you nodding, snarling, or muttering, “Well, he’s not wrong,” then you’re precisely the reader I’m writing for.

You’ll get three essays a week — unapologetically long, occasionally bleak, often funny, always honest. It’s six bucks a month — less than one coffee in Carney’s Canada, or two if you buy the cheap stuff. Everyone says that, of course: “It’s just a cup of coffee.” Fine. But if you’re only going to buy one cup this month, make it mine. It’s $6 a month, and you can cancel anytime.

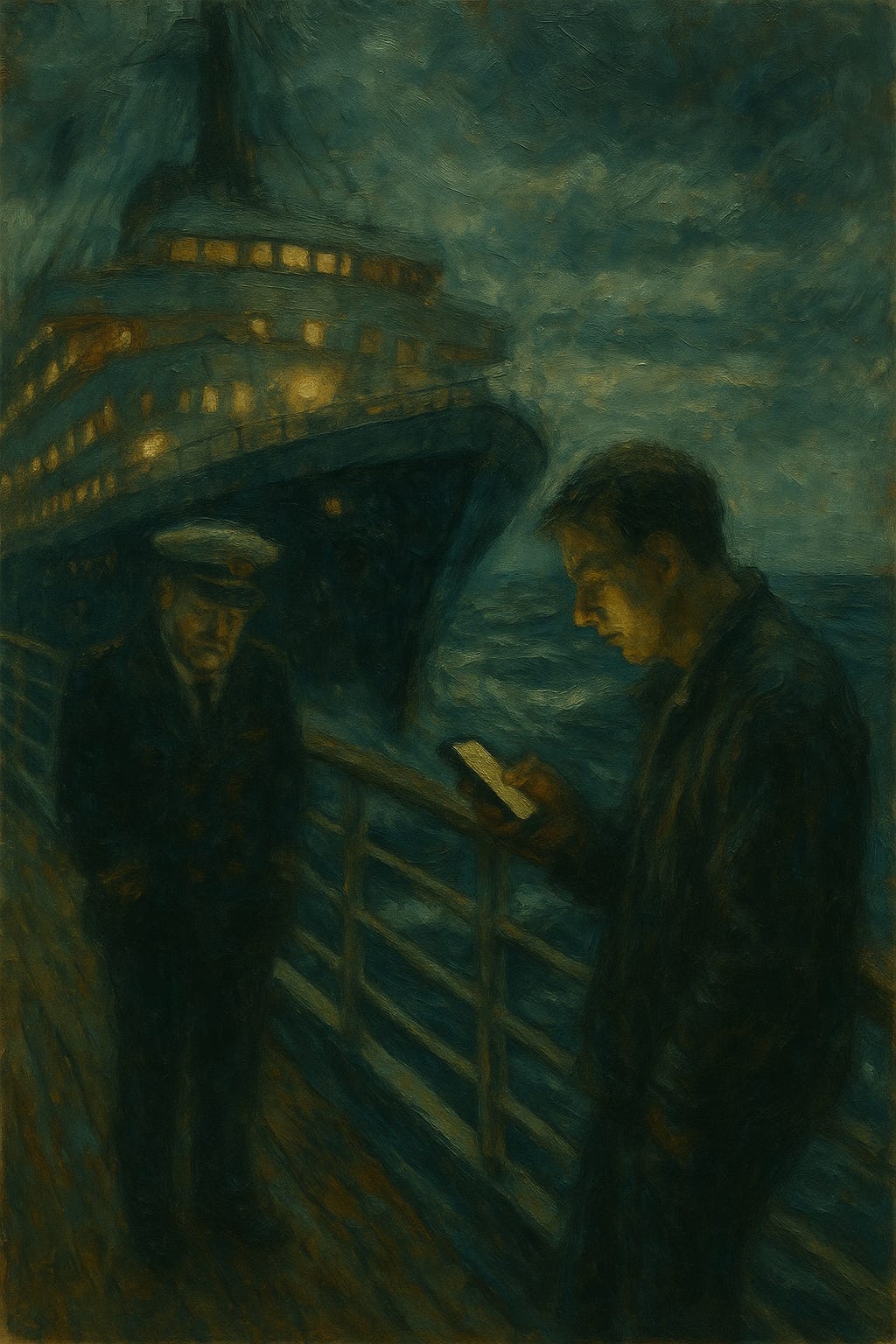

Culture is a great cruise ship that travels silently at night. The buffers and stabilizers cut the waves; if a small movement of an unattended rudder goes unnoticed, the change extends out and leaves us miles off course. It is not the storm that undoes us; it’s the unobserved degree of drift at 2 a.m. by a quarter-asleep helmsman who thinks autopilot counts as vigilance.

Orwell warned that “to see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” The struggle is not merely to see; it is to keep your hands on the wheel when everyone else is bingeing the ship’s entertainment.

If we wake from our night slumber, the breeze is familiar. We come on deck only to say this ocean is no different from the others, perhaps just deeper water, and we return to sleep. We prefer the anaesthesia of the cabin: “It’s all ocean, we are fine, clear destinations are so old school, we have a beautiful ship, the rooms are comfortable, they have Netflix and Prime for free, and no end of activities to fill our time and distract us from ever thinking that direction matters,” the passengers say.

The modern catechism is not atheism; it’s attention-ism. Everything is not permitted—everything is merely diverted. Dostoevsky saw the danger precisely: “The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.”

A ship with no chart is not free; it is merely lost.

Why does the rudder matter? The oceans cover all the earth, don’t they? Do icebergs, rocks, shorelines, and killer storms exist, or are they just a matter of perspective?

Can’t we just post-modern them away?

That is the sly promise: if truth is a mood and reality is a user setting, the reef politely dissolves. But reefs are not notified of our epistemology.

Orwell again: “Political language… is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.”

The same sorcery is applied to culture: rename drift as exploration, call negligence openness, and baptise cowardice as kindness.

Broad culture generates cultural narratives: stories, hopes, shared dreams; they float through the air like pollen and settle in our lungs. As Andy A. West argues, such narratives are emotive first. They subvert the cortex and shoot straight for the viscera.

They are neither inherently good nor wicked; they simply exist, like weather. But like the weather, they matter terribly. They are always untrue in the journalist’s sense—fairy-tale untrue—because, if strictly factual, they would snap under the tension of details.

Their job is not to satisfy a historian; their job is to form a people. Tolstoy put the prerequisite with chastening simplicity: “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.”

Narratives are where we outsource that inner duty to a story we can sing together.

Cinderella—the ur-parable—teaches resilience, decency, and delayed justice: the shoe will fit, cruelty will be exposed, grace will arrive at midnight plus one. We don’t cross-examine the pumpkin; we absorb the moral. The tale bypasses rationality precisely because rationality alone is insufficient for living. Culture is not a laboratory; it’s a liturgy.

Thus, the American pantheon: the Frontier, the Melting Pot, the Civil Rights march down actual streets, the democratic handshake, the rags-to-riches hustler, the exceptionalist promise that effort meets opportunity on a field still being mowed. These are not footnotes; they’re fuel.

They teach people to try. As for Canada, our narratives have been reheated so many times they’ve become tasteless mush.

We practice a reflexive superiority to the Americans while worshipping a medical system like a battered spouse defending her beloved: “He only forgot my surgery because he was stressed.” We glory in hockey gold and then apologise to the air for raising our voice. We are proud to be a country that stands for almost nothing while at times declaring we stand for everyone—a hotel with polite bellhops, not a nation with a mission.

The question before the court is how these narratives are changing—what has replaced the old hymns as church attendance falls and the civic catechisms fray. Can a culture build upon self-indictments and reproaches? Can a civilisation found itself on negatives and stay standing when the wind hits?

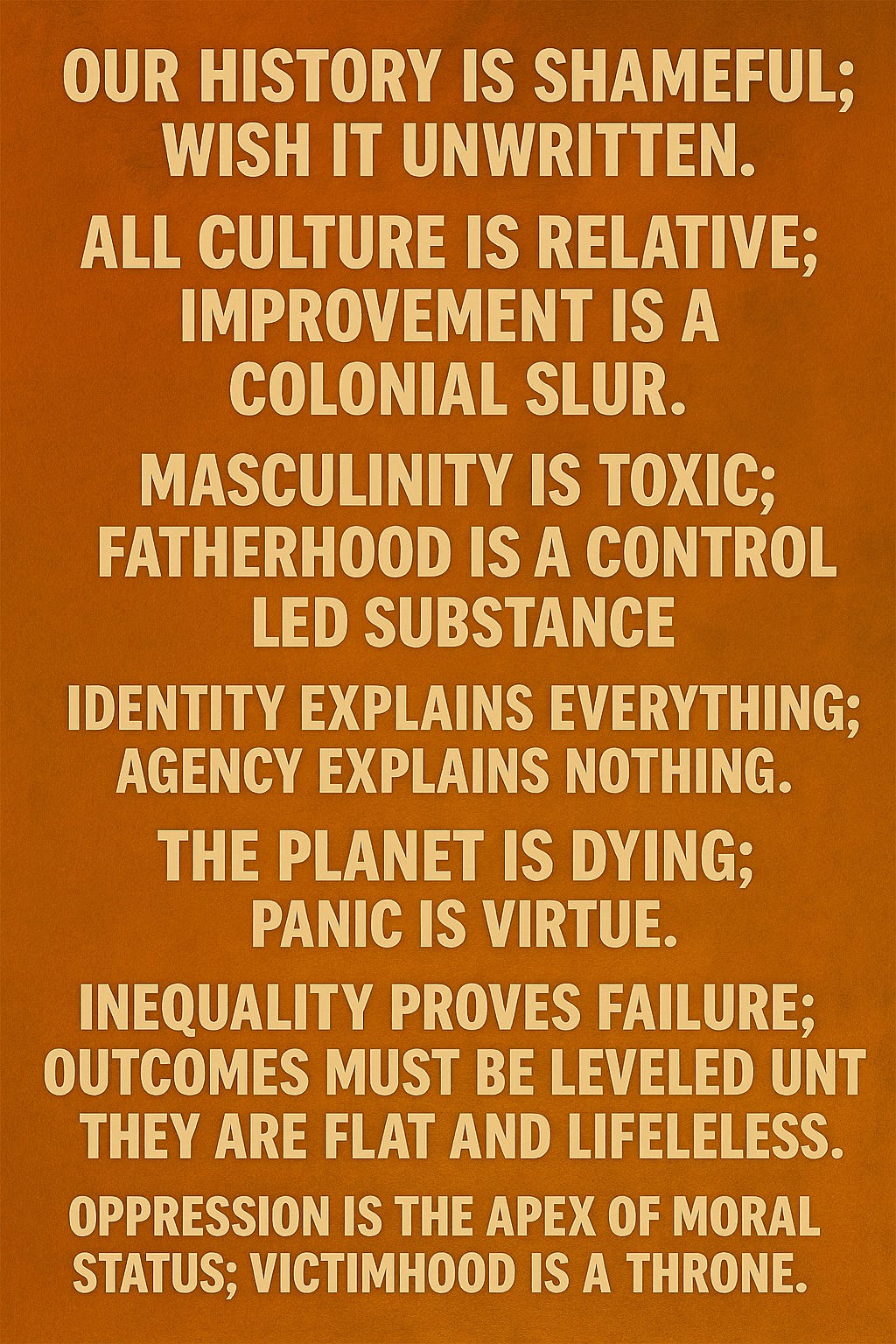

The New Canon, taught with the zeal of a new priesthood, reads like this:

Observe the tone: not aspirational but accusatory. Not a star to steer by but a siren of endless complaint. Show me the happy fatalist; they don’t exist.

Hope is not a garnish—it is the protein. As Chekhov reminds every honest writer, “The task of the artist is not to solve a problem but to state it correctly.” Our new sermons do not even state the problem; they merely lengthen the indictment and call it wisdom.

The intellectuals who sell this miasma retail hubris wholesale: novelty equals progress; subversion equals depth; difficulty equals virtue. They feed on discontent and leave us exhausted.

“Some ideas,” Orwell dryly observed, “are so foolish that only an intellectual would believe them.” Meanwhile, almost half of under-45s, trudging through a curated fog, flirt with the old opium of socialism—apparently unaware of the 20th-century ledger, where the utopian fantasy wrote its name across one hundred million graves.

Tolstoy’s moral axiom still stands: numbers do not redeem wrongs.

These narratives are not foundations; they are solvents. They do not persuade; they inculcate. They impress by repetition and enforce by shame, then screech like smoke alarms when someone opens a window.

Call it “power/knowledge” or “lived experience” if you must, but observe the ritual: pronounce a phrase (“the science is settled”) and assume an incantation has occurred. Dostoevsky’s warning about false freedoms hovers over this: trade your responsibility for security and you will end with neither, and loathe yourself besides.

Consider two sentences. “I believe the pursuit of liberty and truth is noble.” Versus: “Liberty must be clipped wherever someone alleges harm.” The first is a navigational star. The second is a foghorn that never turns off and eventually counts the lighthouse as hate speech.

And then there is the accelerant: social media, that casino of dopamine in which we are not the customer but the product. Its business model is attention arbitrage—strip-mine the limbic system, auction the ore. It atomises friendship into metrics, recodes civic argument as a lizard-brain initiative, promotes comparison, discourages thought, and offers what Chekhov called the most corrosive illusion of all: self-deception presented as intimacy.

(He wrote, “Man will become better when you show him what he is like.”

Platforms do the opposite: they show us what we prefer to be seen as.)

Regulation does not clean this up; it merely adds a minister of propaganda to the stack. Censorship schemes are not prophylaxis; they are the disease with a sash. Of course, markets appeal to base motives as well—but they also separate product from consumer and submit themselves to feedback reality. Social platforms invert that: they make our attention a commodity and teach us to sell it cheaply. The algorithm crawls through the mind like a burglar casing a house, learns the loose window latch, and returns nightly.

Now witness what this does to narratives. The squeakiest grievance gets the microphone; the driest tinder gets the match. The “new stories” take on the structure of fairy tales but without the catharsis.

Imagine The Three Little Pigs recast as a graduate seminar: the wolf is “structural oppression,” the pigs are avatars of intersecting victimhoods. All three are doomed because the syllabus says so.

There is no cunning, no courage, no brick-house triumph—only the moral that the universe is rigged. No child will ask for it twice. As a narrative, it cannot inspire because its teleology is despair.

This is why the old narratives—however corny—worked. They offered a horizon and a hand on the tiller. They said there are shoals and gales, yes, but there are also safe harbours, and you may yet be the helmsman.

They promised not utopia but direction. And direction is the precondition of dignity. Orwell’s austere definition of freedom—“the right to tell people what they do not want to hear”—is useless to a people who have given up wanting anything more than comfort and applause. Chekhov’s admonition that the artist asks the right question matters because the ship cannot be steered by a thesis that questions the existence of the sea.

Only positive cultural narratives—positive not in the saccharine sense, but in the muscular sense of purpose—can be foundational.

Not “everything will be fine,” but “you have agency; now act.” Not “history is a crime scene,” but “history is a record of the human struggle to improve.”

Tolstoy’s mirror again: change yourself; then you may change the course. Dostoevsky’s demand again: find something to live for or you will live for nothing, and call the vacancy enlightenment.

So, back to the helm at 2 a.m. The officer of the watch does not need a TED Talk; he needs a heading. The sun is below the horizon, the radar hums, the watchstanders sip coffee, and the gyros whisper.

The sea does not care about our feelings; the shoals are indifferent to our hashtags. We must keep the narrative that keeps the hand on the rudder: the world is not just endless water; the waves do not extend forever; there are rocks, and there are also bright, noisy ports where children shout and the baker rises early.

We steer or we drift. We tell better stories, or we are told to sleep.

“Who controls the past controls the future,” Orwell wrote, and “who controls the present controls the past.”

The inverse is also true: a people with a future worth sailing toward will not surrender their past to those who hate them, and they will not let the present be managed by those who prefer the engine room to the bridge.

Set a course. Trim the sails. Post a lookout. And for the love of honest literature, stop calling despair a philosophy and drift a destination.

Fascinating and insightful.